It’s Not “One and Done”: Ongoing Conversations About Illness

These conversations are hard—for you and for your child. But they are important. We want to avoid them as long as possible, but on the other hand, we want to be the authoritative word for our children to guide them more than peers or media.

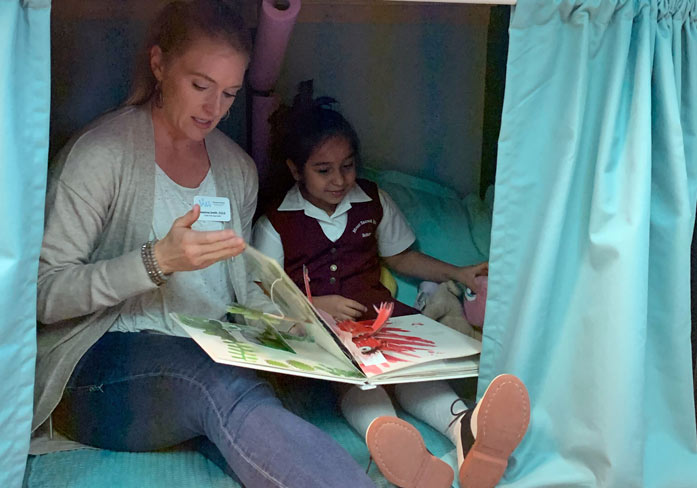

By Crystal Wilkins, M.Ed., LPC, RPT, CCLS, CEIM, Wonders & Worries child life specialist

When having critical conversations with children, parents and caregivers often want to have the conversation once and move on. Whether it is a conversation about illness, death, bullying, body image or sex, we’d rather move on as quickly as possible.

Why? If we are honest as adults, these conversations create anxiety in us. How do we say these words? Will I say it “right?” How will my child react? Will I make them worry more? What questions will they have for me? Do I really have to say that word?

These conversations are hard—for you and for your child. But they are important. We want to avoid them as long as possible, but on the other hand, we want to be the authoritative word for our children to guide them more than peers or media.

Start Early & Keep Talking

If we are to engage in these conversations, I have two mottos: 1) Start talking earlier rather than later, and 2) Keep having the conversation.

From a developmental perspective, we know that children need information repeated so they can remember, process and synthesize the information into something useful. We also know that children need practice to master new skills, from tying their shoes to learning how to regulate their emotions.

So when engaging in a conversation that is emotionally heavy, uncomfortable, or complex, give information in small chunks first. Then proactively review the information on a routine basis – weekly or monthly.

Talking About Illness or Injury in the Family

Talking routinely about a parent’s illness or injury can take several forms. A few ideas include:

Family meetings—Set up a time that works for all members of your family to review what has already been shared and to give updates. This can be weekly or monthly, but is a touchpoint for your children to know that they will be included when new information is known. You can name the meeting, host it in different rooms, making it a walking meeting or plan a special food for these conversations. I knew a family who held “Snuggy Time” on Sunday nights, where everyone piled into the oldest child’s bed with their favorite stuffed animals to talk.

Communication Tools—Find creative ways for children to continue to ask questions. Examples:

- Wonders & Worries Jar—We routinely do this activity with children at Wonders & Worries. Fill a mason jar with strips of blank paper. Let the child write down or draw new questions or new worries they have on the paper and put them in the jar. This prevents a child from forgetting their thoughts and questions, and it also gives them a safe outlet if verbalizing fear is too difficult. Writing or drawing may be more manageable.

- Symptom Checklist – This tool could be used at family meetings or week to week with children as young as 2-3 years of age to review how illness or injury is impacting mom or dad. What are the children seeing and what are their perceptions about those things? Each time you use the checklist, you can add more education and information and/or just provide the repetition children need to successfully learn and process.

- Puppet or Stuffed Animal Medical Play – Have them give their stuffed animal, doll or action figure a “check up” and see if they have any of the parent’s symptoms. Sometimes, when a child uses a fantasy item to explore themes of illness, they are more open because it does not directly mimic what is happening for them in reality (though it mirrors it). The metaphor of play gives a safe distance to explore things more fully.